From Kingston to Notting Hill

The journey of Jamaican soundsystems to the world

Pictured: Billionaire Boys Club AW25 Campaign

Over the past years, we’ve seen a rise in soundsystems and listening spaces being incorporated into fashion brands’ creative campaigns and physical spaces. Asics x Bandit’s “Sound Mind Your Business” campaign features a large hi-fi soundsystem as a backdrop, Carhartt WIP is installing large soundsystems in stores worldwide, and most recently, Billionaire Boys Club’s Fall/Winter campaign, which celebrates Jamaican soundsystem culture.

As Notting Hill Carnival is coming up in London, we’d like to take a moment to look back at the history of soundsystem culture and its journey to the world stage.

SOUND by Aimé Leon Dore

What are soundsystems?

Traditionally, a soundsystem is a combination of DJs, sound engineers, MCs, and a set of sound amplification systems and custom-made speaker boxes to fit the collective’s sound. In the early days of soundsystems, the collectives would not purchase the hardware from shops. One would have to reach out to or be put in direct contact with sound engineers or amp builders to have custom speaker sets made to their requirements.

Since every amp and speaker was custom-made, building a soundsystem was a very intricate process that paid attention to every single auditory element of the final product.

Before soundsystem culture became more prominent and sizable, collectives would focus on having their soundsystem tuned to specific frequencies to guarantee they not only deliver loud volume, but quality sound first and foremost.

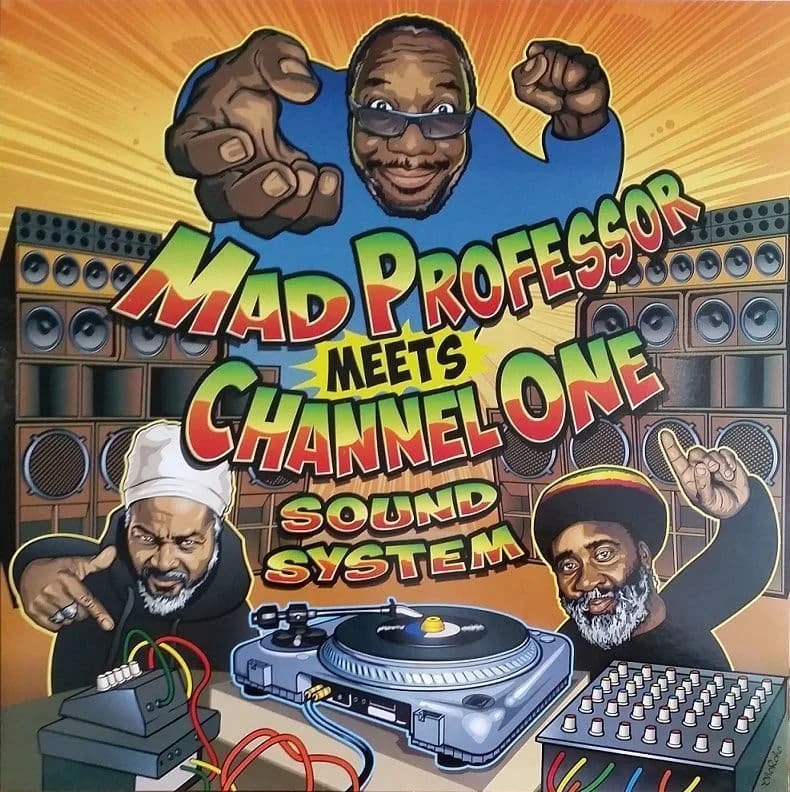

Channel One soundsystem

The birth of the soundsystem: a Jamaican innovation

Tom Wong, a Chinese-Jamaican businessman and DJ, is credited with founding the first commercially successful soundsystem named ‘Tom the Great Sebastian’. Widely regarded as the blueprint for modern soundsystems, Wong played a crucial role in popularising Dancehall music, although he initially played imported Rhythm & Blues from the US.

Under British colonial rule Jamaicans weren’t allowed to participate in dances uptown, so local DJs took to the streets on trucks loaded up with generators, turntables, and large speakers stacked on top of one another. These street parties represented something much larger; they were a form of resistance.

Before building the Great Sebastian, Wong used an RCA PA (an advanced speaker with a mixer and amplifier) to perform at dance halls and street parties.

One day, as Wong was playing for an event at a significant dance hall in Kingston named Jubilee Tile Gardens. Across the street was a radio-repair shop and record store owned by none other than Hedley Jones, a pioneer of Jamaican music history.

Jones used his hand-built amplifier strictly to promote and advertise the records he was selling. The first of its kind in Jamaica, Jones’ amplifier was designed to be able to enhance the low, middle, and high frequencies and remix them. Wong’s PA was overshadowed by Jones’ amp.

Within a few days, Wong approached Jones to build him a similar amp and coined the term “soundsystem”. Since then, Jones had gone on to build other notable soundsystems such as Duke Reid’s Trojan, Roy Johnson’s House of Joy, and Coxsone Dodd’s Downbeat.

Duke Reid’s Trojan soundsystem

All of the soundsystems, similar to the Great Sebastian, started off playing imported tunes such as American Rhythm & Blues or Cuban Mambo. With new soundsystems making their way to the streets of Kingston, DJs and crews started competing with each other and led us to the first sound clash where two crews would battle to see who had the best selections and sound.

It was only towards the late 1950s that there was a slow shift towards new local genres such as Ska, which laid the groundwork for other genres such as Rocksteady and Reggae to emerge later on.

From Community Protest to Global Celebration: Notting Hill Carnival

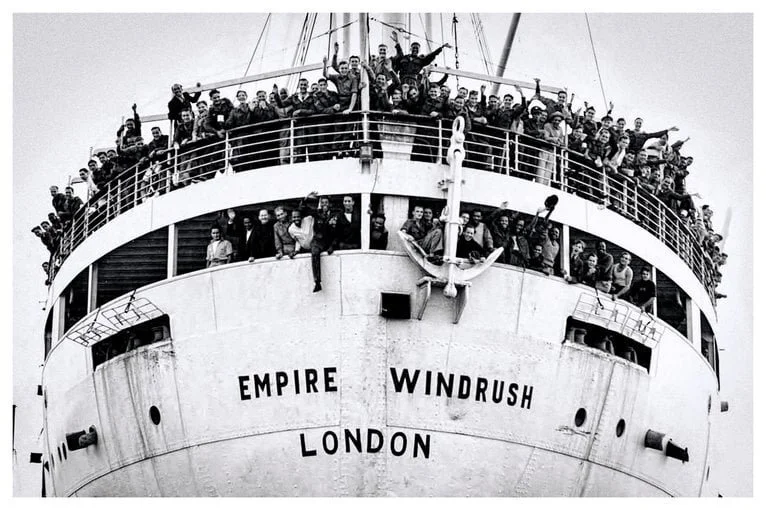

Between 1948 and 1973, Britain aimed to fill its post World War II labour shortage by actively recruiting people from its colonies in the Caribbean to migrate to the UK for cheap labour. The generation that answered to this call, often referred to as the Windrush Generation, was named after the HMT Empire Windrush ship that arrived in England in 1948 with over 1000 immigrants from the Caribbean. These people arrived in Britain that promised opportunity but delivered systemic racism and hostility.

Empire Windrush, 1948

Nearly a decade later, as Caribbean communities took root in boroughs like Brixton and Notting Hill, they were met with a violent backlash.. Far-right movements like the Union Movement incited racial hatred, encouraging white working-class Britons to attack their Black neighbours in an attempt to “keep Britain white”.

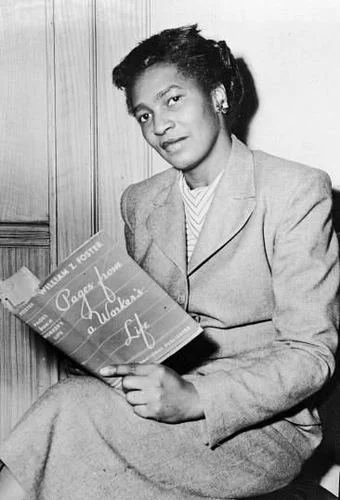

The murder of an Antiguan carpenter led Claudia Jones, a Trinidadian activist, to organise a Carnival in 1959 as a means of showing support and solidarity with the Caribbean communities in London. By 1966, other activists were inspired by Jones to organise street festivals in an effort to ease ongoing tensions in the boroughs. To encourage the local Caribbeans to participate, the festivals slowly turned into Carnivals through the addition of more Caribbean Carnival elements like processions and steel pans. This marked the beginning of the annual Notting Hill Carnival we know today. Nearly a decade later, the carnival became more pan-Caribbean and celebrated a wide range of cultures from all across the region.

Claudia Jones, 1948

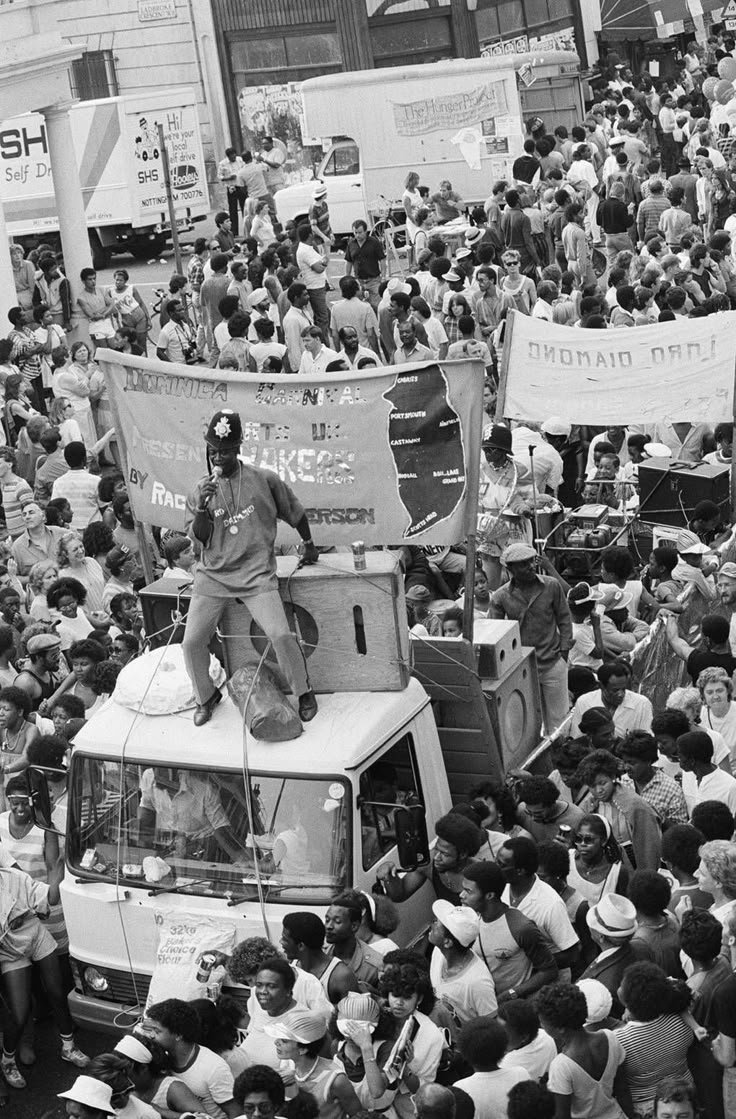

Soundsystems were invited to be an official part of Notting Hill Carnival in 1973 and have since then become an integral part of the festivities with over 30 different Soundsystems, including legendary acts such as Channel One Sound System and Aba Shanti-I.

Notting Hill Carnival, 1984

Mad Professor x Channel One Soundsystem flyer